For B0ardside6, we have a backyard installation of analog video synthesis, by Sean Russell Hallowell a local composer and audiovisual artist.

I first met Sean at an AVClub SF meetup, hosted at Syzygy, an awesome community art space in the Mission district. His talk stood out from the crowd of digital artists, as he was demoing his custom analog video synthesizer. Amazingly it turns out, he was actually quite new to the world of video synthesis, having thrown himself into learning how to build circuits during the pandemic. His background is in the history and literature of compositional tradition in European music of the Middle Ages and Renaissance! “the phenomenology of time in relation to those divisions of Medieval philosophy known as the quadrivium — i.e. music, arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy.”

Ok! Middle Ages and Renaissance! Tell us about your background first!

Yes, it all starts with Pythagoras. Been a musician all my life, played guitar and saxophone growing up. From the Pacific Northwest, so I listened to a lot of grunge. Went to college not knowing what I was getting into and a few rabbit holes later got a PhD in Medieval music theory. On one hand I was reading a lot of literary theory and philosophy, and on the other I was discovering music on the “experimental” end of the “classical” spectrum.

In particular I was listening to a lot of Modernist stuff that, I soon learned, has more in common formally with French and Flemish music of the 15th and 16th centuries than anything that came right before it. It so happens that, against all odds, that music (i.e. vocal polyphony from France and the Low Countries for Catholic religious rites) slays, and sounds awesomely alien if all you’ve ever heard are tonal progressions in 4/4 time.

To seal the deal, I was brainwashed by Medieval music theory, which is more physics-plus-self-help-doctrines than it is recipes for how to compose. Medieval theorists all explain the power of music in terms of cosmic harmony, sympathetic vibration, spiritual attunement, and so on – which is, if I may say so, objectively true. So I don’t see how it could have gone otherwise for me.

And how did you get from Quadrivium to Video Synthesis?

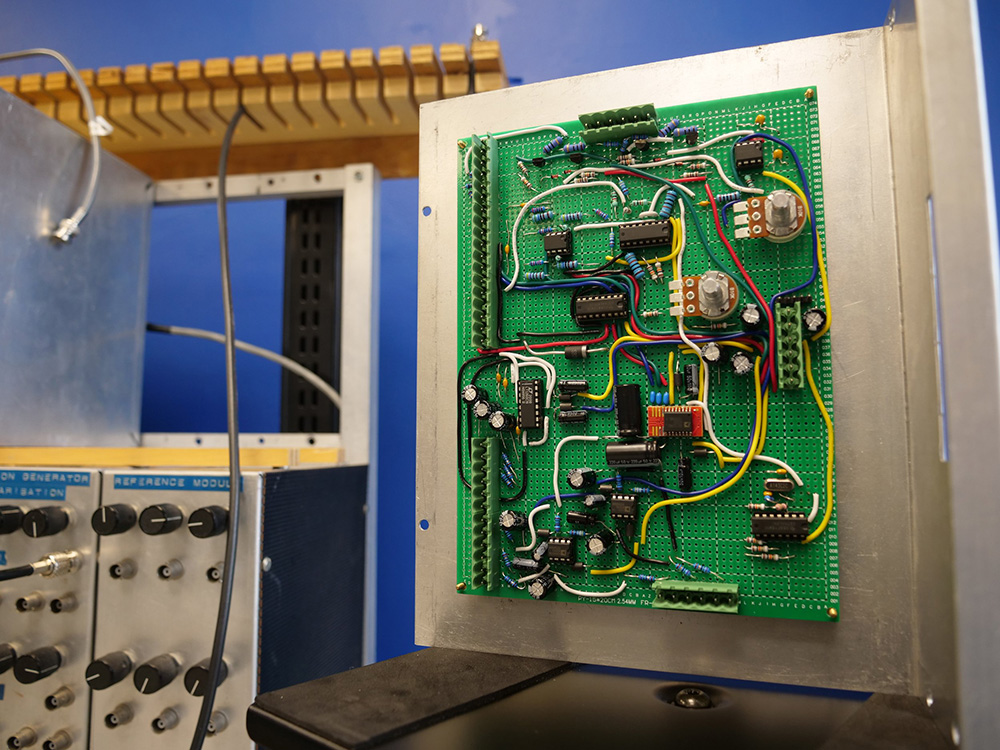

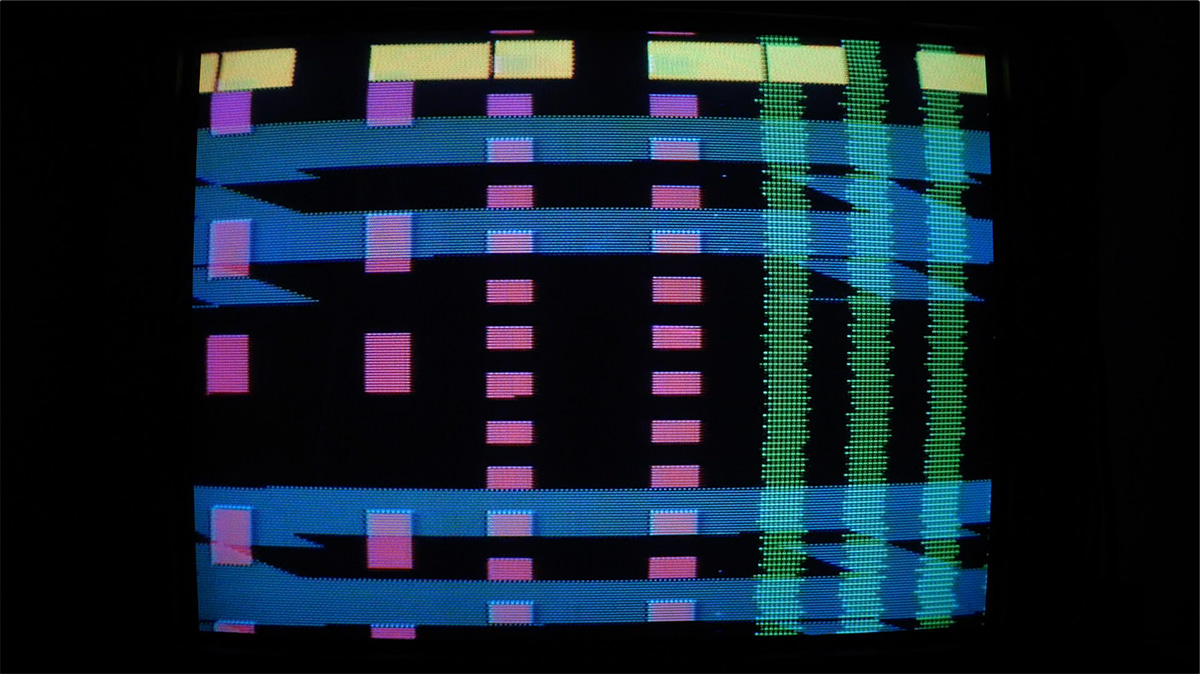

Basically a convergence of otherwise random threads. Growing up in the 80s and 90s I am hardwired to be hypnotized by cathode-ray tube TVs. At some point I got into building my own audio synthesizers, which for experimental reasons I started plugging into CRTs. This is how I had the realization that the same voltage that makes a speaker jump can also make patterns appear on such a monitor. There’s a bit more to it than that, of course, so I went deep and read all the technical manuals I could find for analog video gear from the 70s and 80s. Eventually I taught myself how to generate the type of signals needed to make a CRT happy. The more I worked like this the more I realized that what I was actually doing was “visual music.” You can generate patterns that manifest as one aesthetic phenomenon in one domain but may appear as very different phenomena in another.

All this coincided with an artist residency I had in summer 2021 in the Icelandic town of Ísafjörður. I lived there for two months taking audio and video recordings of the natural environment. At the end of my residency I staged a large-scale installation incorporating my first hand-built synthesizers. That work mixed synthesis patterns with all that natural footage, which got me onto this idea of isomorphism between micro-temporal (video synthetic) and macro-temporal (geological) structures. Which is, of course, very Medieval.

When reading your background, I see you recently worked on restoring a Sandin IP - I had to look up what that was - Dan Sandin built the first video synthesizer in 1973 - “as a modular, patch programmable, analog computer optimized for the manipulation of gray level information of input video signals..“ I love finding out technology origin stories! How did that project come about? Can you tell us a little about the background of the Sandin Image Processor and its importance in video art?

Yeah, I have worked on a couple IPs at this point – one at a place called Alfred University in New York state, the other at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Basically the IP is the first real tool for analog video art, designed and constructed back when composite video as a signal architecture was still a new thing. As you mention it’s basically a modular synth that processes external video signals along with on-board oscillators to produce a wide array of luma and chroma effects. I had actually never heard of it before I built and designed my own modular video synth from scratch, because I tend to be an ostrich about things I’m working on. I was teaching an analog video workshop and one of the participants (fellow video artist Stephen Radley) told me about the Alfred IP and how it had a broken color encoder.

Being uniquely qualified to build a new one, I went out for a couple weeks and got the feel of the machine. When word got out that I had fixed the Alfred IP I was contacted by SAIC which also, it turns out, had an IP with the same problem. So I built an encoder for that one, and have since been back to service it as well. IPs were built from scratch by art departments at universities back in the 70s and 80s and only a handful of working ones survive. So it’s a real privilege to work with them now, and great to see the machines actually getting used by people who are new to video art.

You mentioned you were also in bands while you were in academia. What kind of music were you making? Rhode Island had an awesome art rock scene around the 2000s with Lightning Bolt and Black Dice - did your time at Brown cross over with that scene?

It did! Saw Lightning Bolt live more times than I can count – still listen to those records. My band back then was called the Stay at Home Dads – somebody once described us as demented circus rock. We played at all the local venues and a few more underground spots around campus. Providence was (and still is, I hear) the place to be.

How do you see the connecting dots between video and sound, technology and space?

Not sure how I can answer such a good question without writing another dissertation, but here it goes: I aim to bring auditory and visual phenomena into dialogue in such a way that you experience them differently than if they had been presented on their own. This usually involves playing with synchronicity and asynchronicity in ways that make you interrogate notions of causality and simultaneity. For instance, questioning if a sound caused an image, an image caused a sound, or if they were causally unrelated. This has parallels in Medieval music too. There are some textures that are closely coordinated among all the voice parts, and some that feel random – though these latter are usually the result of some underlying processes that have their own logic, just not one audible at surface level.

It is of course possible to explore all these things in a fixed media work, but when it’s situated in a specific space there’s another dimension to the experience. As for technology, without opening too big a can of worms I’d say I’m always keen to highlight how technique and technology are mutually reinforcing. The tools you use have a determinant effect on what comes out of the artistic process. I use this to remind myself to let go of the myth of a blank slate and accept that everything starts from something.

You use handbuilt circuitry - how important is it in your work to build your own tools? Is it a DIY philosophy or are you driven more by the enjoyment of learning?

Definitely both. At the end of the day, I just can’t get into certain tools that are commercially produced. There are exceptions, like the keyboard that I used growing up, which has all those great 80s drum presets that I’ll never get sick of. But with video, so much of what drives my art is encountering the technology at its most basic level and building things from the ground up. Effects and techniques that I rely on extensively grew directly from learning how to alter fundamental properties of a video signal to produce specific results. As I’m sure you feel about your custom system for audio synthesis and performance that you built, at a certain point you want to decide what you can control and what you don’t need to control, and there’s no other way to achieve that other than doing it yourself.

How do you approach installation work differently from a system for live performance?

The number one difference has to be attentiveness to the environment. Sure you have to optimize your set for a venue or whatever but when it comes to an installation the big thing for me is always to see how I can work with what I already have. In that Iceland installation I mentioned, the venue had a bunch of full-length dance mirrors sitting around that I used to make an immersive space around my CRTs and multichannel speaker setup. Similarly, in an installation I did at Artists’ Television Access in SF, I was working in a window gallery that offered an opportunity to arrange TVs more sculpturally, which I let guide the composition.

How has San Francisco shaped your relationship with art? What about the Sunset neighborhood?

Well, having grown up in Oregon I’d say the natural environment in this part of the world is baked pretty deep into my bones. Nature as cosmic music, etc. As for San Francisco the city, for the longest time I didn’t really feel a part of any scene – it was through AV Club (which you know well!) that I started connecting with more like-minded artists. This has been great because although my stuff isn’t properly “digital” I still find the analogs between what I do and what digital artists do to be very thought-provoking.

As for the Sunset, at the risk of outing myself, I’ve actually just moved to the North Bay after six years in the middle Sunset (first on Judah, then off Noriega). This 100% for more space reasons, since I have always loved and will always love the Sunset. Living that close to the beach, walking the Great Highway, feeling the fog roll in, that was my way of tuning in every day to the music of the spheres. Since the ocean is just an instrument being played by the moon’s gravitational pull, that is. Again, a very Medieval reason.

You’ve built your own platform for online learning, running a series of live art and engineering courses. Can you tell us more about how that began, the range of courses, and what’s planned for the future?

For sure. I do a couple of different things in terms of teaching art and electronics, ranging from workshops about circuit bending and audio synthesis to ones about analog video processing. My interest in teaching comes from the fact that “engineering” and “art” are things that you can learn separately but are not usually taught in a mutually reinforcing way. The idea when I teach is always to highlight the artistic aspects of engineering your tools and the technical aspects of making art.

On the horizon are more in-person events, which I’m very much looking forward to. I find learning around others in a physical space makes a big difference – especially when it comes to electronics. Leading workshops will always be a part of my artistic practice since I learn as much as anyone else does through running them. Being self-taught, I feel I don’t really understand something until I have to explain it to someone else.