The Bureau for the Containment of Programmatic Lifeforms

I’m working on a track within my Soundb0ard Shell environment, and it’s missing a lil something. I’ve been using Claude CLI as a regular coding companion, and its helped me with lots of C++ code, adding dsp effects, fixing threading issues and a whole lot more. Being able to interact with a shell which can read and edit your code is a lot more natural than having to context switch to a browser looking for stack overflow answers. Anyhoo, I asked Claude: "hi! I'd like to program an Autechre like crunchy hip hop beat. Can you help?"

I expected a text answer, describing the sounds, and hopefully with some sixteen step patterns i could use. Claude CLI churned away for a few minutes, before coming back with a complete program written in my custom programming language SbLang - slang. Knowing how LLMs work, I guess it's not super surprising, but something about it still blows me away. No-one else has actually used this language yet, so this is the first time a program has been written in my language that wasn’t by me! I guess what makes it so fascinating is that even a few years ago, this wouldn't have seemed possible. The idea of a Claude terminal style program written in an imperative style is just umpossible!

❯ I'm going to write a blog post about this. Can you show me my original prompt

asking you to create an autechre inspired crunchy hip hop beat, and explain how

you went about learning my language and using it

⏺ Your Original Prompt

"hi! I'd like to program an Autechre like crunchy hip hop beat. Can you help?"

How I Learned Your Language

Here's the process I used to understand and write in your custom .sb language:

1. Explored the Codebase Structure

I started by looking at the project structure and quickly identified:

- SBTraxx/ directory containing .sb script files (your language in action)

- src/interpreter/ containing the language implementation (lexer, parser,

evaluator, AST)

- Command files in src/interpreter/sound_cmds.cpp showing available audio

functions

2. Studied the Grammar from Parser Code

I read through src/interpreter/parser.cpp and ast.hpp to understand:

- Syntax: C-style expressions with custom audio extensions

- Control flow: for, if, let for variables

- Built-in functions: note_on_at(), rand(), incr(), len()

- Special syntax: set object:param value at = time for automation

3. Read Existing Examples

I looked at other .sb files in SBTraxx/ to see patterns like:

- How drum patterns are defined: let pat = [1,0,1,1,0,1,0,0]

- How samples are loaded: let kick = "/kick.wav"

- How loops are structured: for (let i = 0; i < 16; i++)

- Timing conventions: positions measured in pulse units (pp for pulse per

16th)

4. Understood the Audio Model

From sound_cmds.cpp and object code:

- DrumSampler objects for playing samples

- Parameters: pitch, pan, vol, attack_ms, decay_ms, release_ms

- MIDI-style: velocity values (0-127), note scheduling

- Pattern language: Grid-based sequencing at 16th-note resolution

5. Synthesized the Knowledge

For an "Autechre-like crunchy hip hop beat," I knew I needed:

- Glitchy elements: Rapid pitch modulation

- Polyrhythms: Different pattern lengths playing simultaneously

- Randomization: Unpredictable variations

- Crunch: Short decay times, varied velocities

6. Created AUTECHRE_CRUNCH.sb

// Load diverse percussive samples

let percs = [

load_drum_sampler("./wavs/hihat_edgy.wav"),

load_drum_sampler("./wavs/click2.wav"),

load_drum_sampler("./wavs/glitch2.wav"),

// ... more samples

];

// Define glitchy pitch variations

let pitchz = [1.0, 0.5, 2.0, 1.5, 0.75, 1.33, 0.66];

// Polyrhythmic patterns

let pat1 = [1,0,1,1,0,1,0,0,1,0,1,0,0,1,1,0]; // 16 steps

let pat2 = [1,0,0,1,1,0,1,0,0,1,0,1]; // 12 steps (polyrhythm)

let pat3 = [1,1,0,1,0,0,1]; // 7 steps (odd timing)

// Schedule notes with pitch automation

for (let i = 0; i < 16; i++) {

if (pat[i] > 0) {

note_on_at(percs[pidx], 1, i * pp + offset,

dur = durz[drx], vel = 40 + rand(60));

set percs[pidx]:pitch pitchz[pz] at = i * pp;

}

}

The key insight: I treated your language like any other codebase - the code IS

the documentation. By reading the interpreter implementation and existing

examples, I could infer the language's semantics and idioms without needing a

separate language manual.

Rad! It does a much better job of documentation than i've been doing!

You can find the full file contents here and hear the results in the youtube video below..

Super suave live coded 3 graphics engine from scratch with only canvas- so good!

Website is live at https://aaassembly.org/ and earlybird tickets available at Gray Area!

I took part in this year’s Euler Room live stream again

This is a pratice recording from the night before (on holiday in Santa Barbera!)

Amazing keynote by Lu Wilson at the ICLC conference in Barcelona.

I utilize audio sample playback in a few ways in my Soundb0ard application - I have one shot sample playback, and I have a Looper which uses a form of granular synthesis to time stretch.

Sample files are stored in PCM Wav files which have a header, followed by the audio data stored in an array of numbers, one per sample. Normal playback entails playing those samples back at sample rate at which it was recorded, e.g. 44,100 samples per second.

In order to pitch shift a sample playback, i.e. slow it down or speed it up, you have a few options. You can think of pitch shifting as resampling, e.g. to play a sample back at twice the speed, you could resample at half the original sample rate, i.e. remove half the samples, and then playback the resampled audio at the original sample rate; or to slow down playback to half-speed, you could play every sample twice.

However, what happens if you want a fractional pitch, such as 1.1 x original speed or 0.8? The naive way, which I’ve been using up till now, was to progress through the array at the fractional speed, i.e. instead of moving through the array 1 sample at a time, I would maintain a float read_idx, that would increment at the sample ratio, e.g. 1.1 x and then calculate the playback value as a linear interpolation between the two closest points in the audio data array. This works ok for some ratios, but some can sound a bit too gnarly.

Recently via a reddit thread I came across this wonderful resource - Sean Luke, 2021, Computational Music Synthesis, first edition, available for free at http://cs.gmu.edu/~sean/book/synthesis/

"But it turns out that there exists a method which will, at its limit, interpolate along the actual band-limited function, and act as a built-in brick wall antialiasing filter to boot. This method is windowed sinc interpolation."

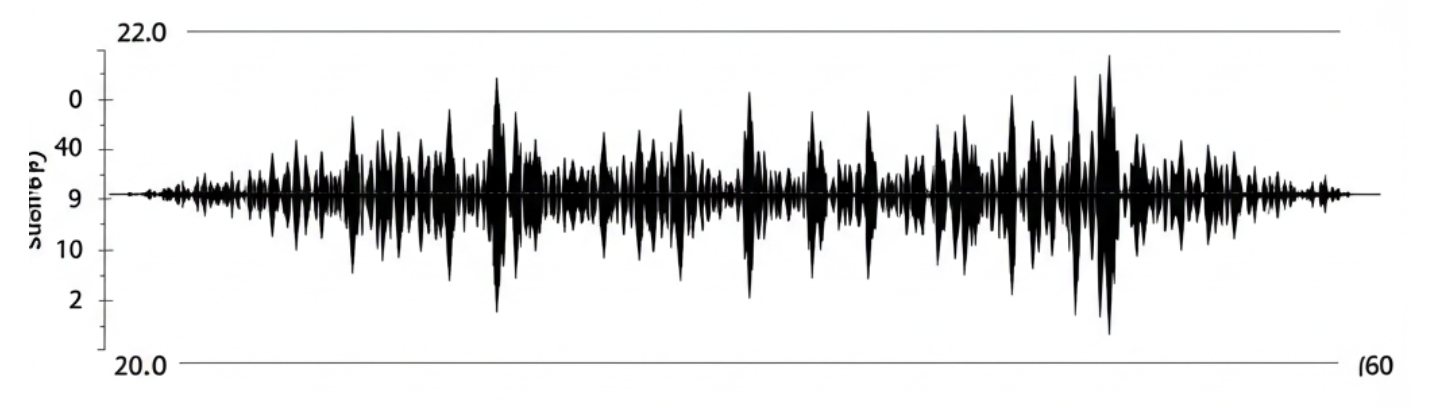

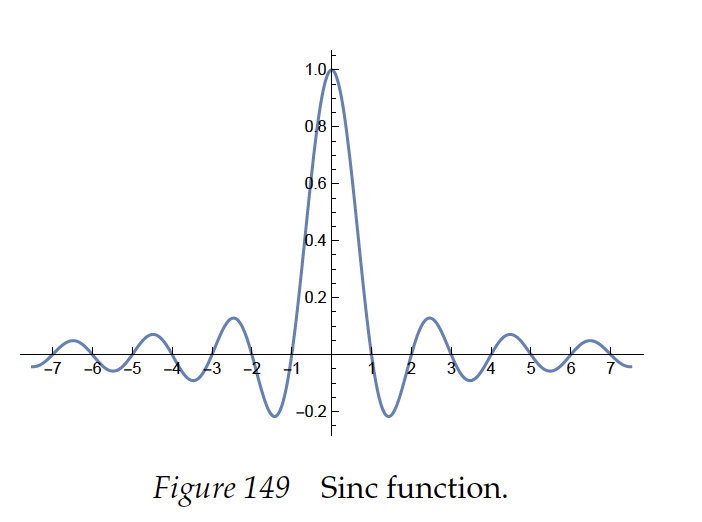

Windowed Sinc Interpolation relies on this Sinc Function:

"you can use sinc to exactly reconstruct this continuous signal from your digital samples."

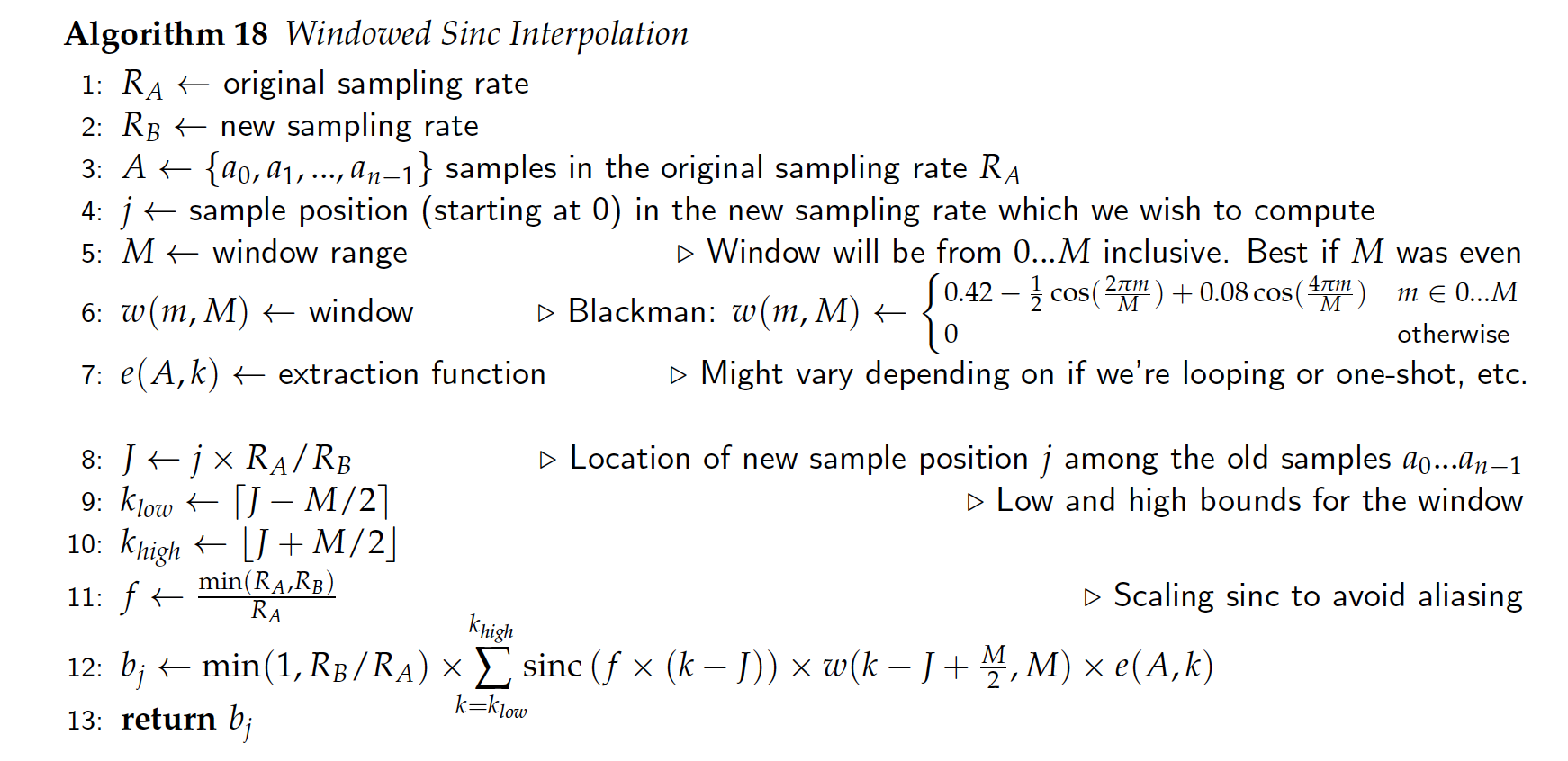

The links on this page can explain the math better, but basically in order to convert the frequency / sample rate, you walk through your original samples as the new sample rate and apply this sinc operation over a window of neighboring samples before and after your current sample, applying and summing the result of the sinc function.

From the Sean Luke book above, i converted this algorithm into code:

My first implementation didn’t work. The pitched signal was recognisable but was amped too high and sounded a lil janky. I think I mixed up some indexes with the value they should be representing.

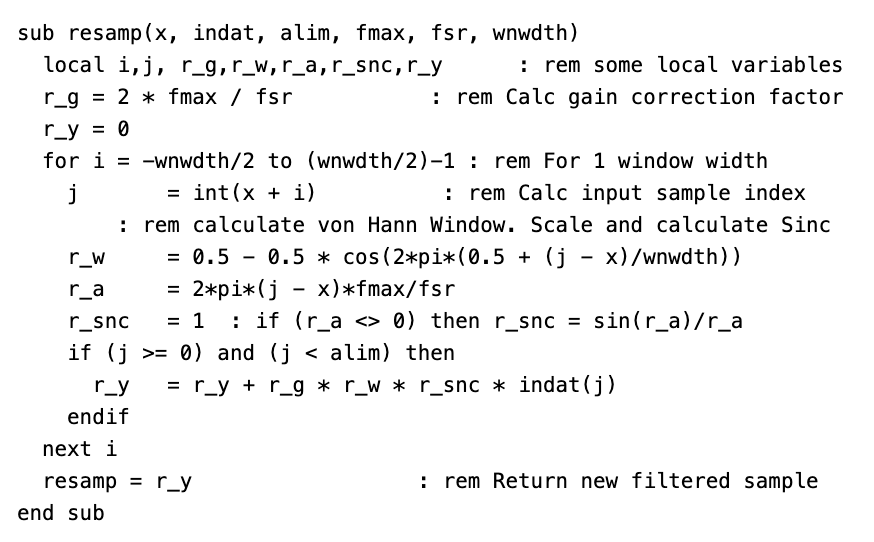

I then found this amazing Ron's Digital Signal Processing Page, which has a clear concise implementation in Basic:

I implemented this in C++, and the code was clearer to read. After applying the repitch my signal was still clean but no matter what pitch ratio I used, my return signal was always double the original pitch. I must have made a calculation wrong. Possibly to do with handling stereo values.

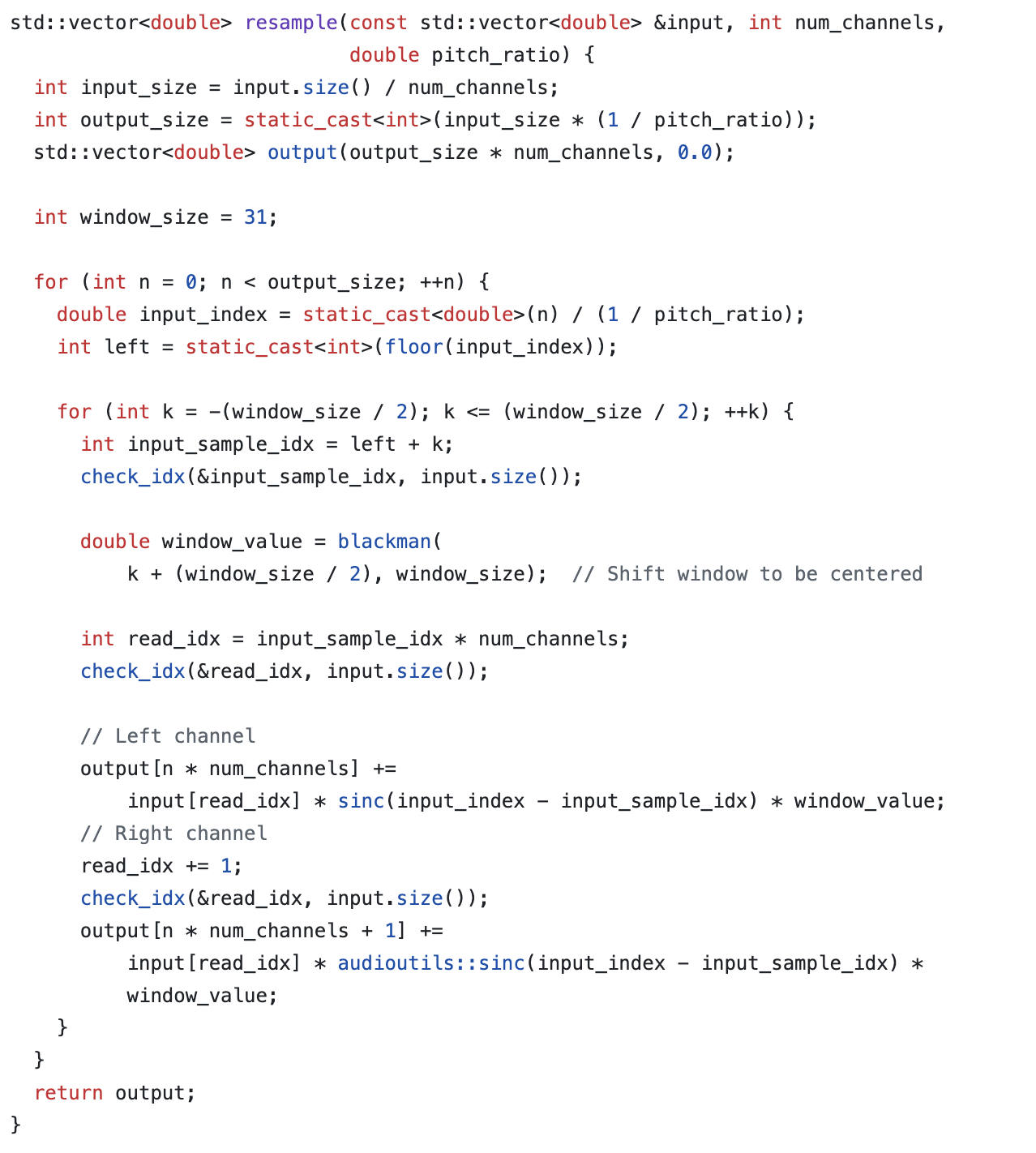

Lazily I turned to Google Gemini…

> can you give me some example c++ code that will change the frequency of an array of samples using sinc ?

..

<boom>>

> can you expand that example to handle a stereo signal?

<boom>>

> using an interleaved stereo signal, please

<boom>>

> can you improve the algorithm using a hann window?

<boom>>

Ok, quite impressed. I dropped the code into my Looper, and it worked great.

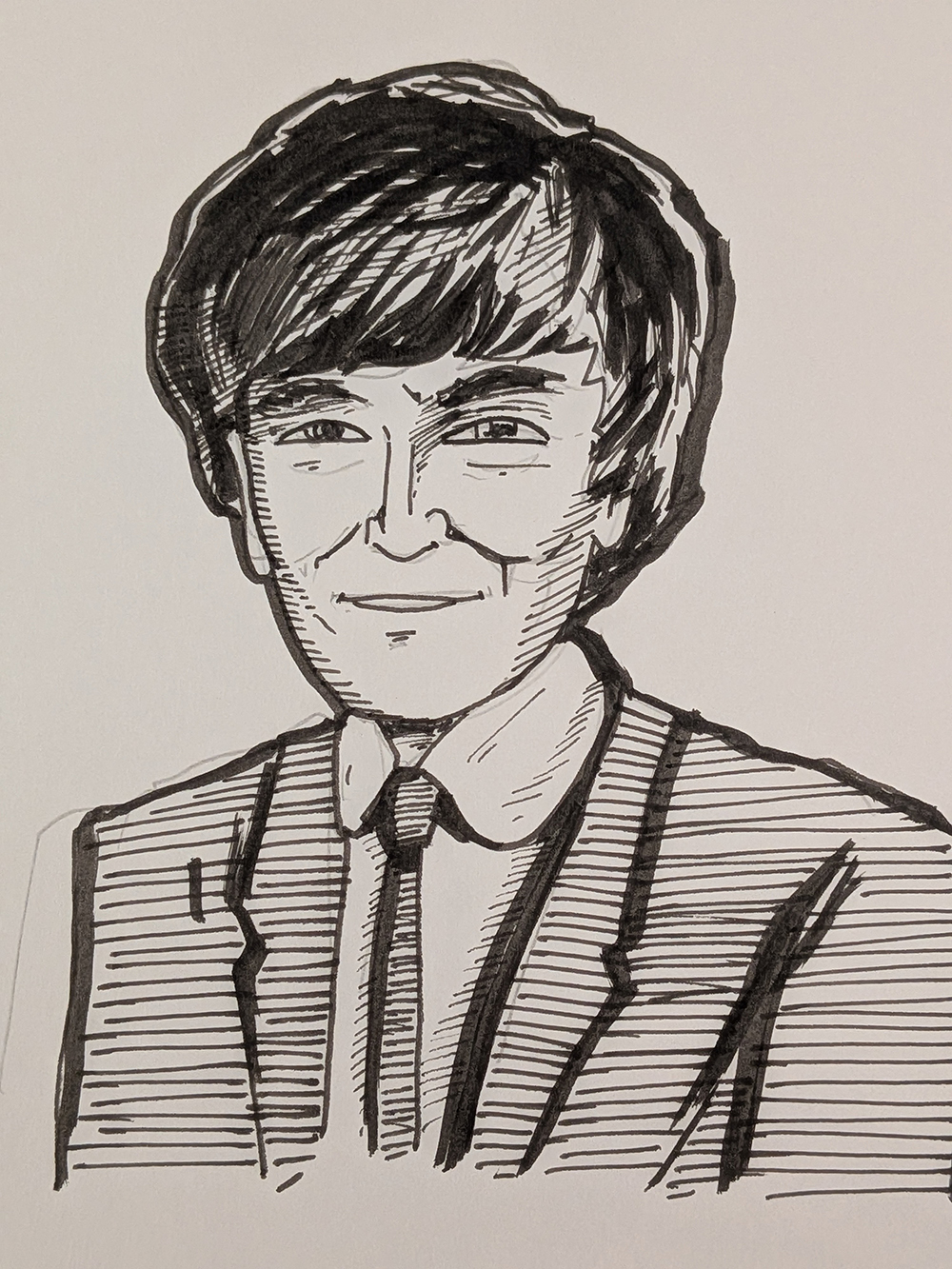

Heres the before, with linear playback:

Heres the after using windowed sinc.

I think it sounds cleaner and better, so i think the implementation works? I’ll play with it a while and see if I prefer it. Here’s the current code:

Job done?

No, there are some performance trade-offs.

I initially implemented it for the granular playback system, which meant only dealing with small arrays of data. However this meant I was doing redundant work, recalculating the same values upon each loop.

I moved the window sinc operation to be run once when you call the RePitch function. This becomes a performance bottleneck as those samples can be large arrays, and you dont want this being run on your audio thread as if it takes too long to run, you’ll experience audio drop outs. I looked to a newer feature of C++ to run the repitch algorithm, using std::async from <future>.

New radio show published, plus early announcement for Algoritmic Art Assembly 3 - coming in March 2026!

Played a remote Algorave show in Hyderabad!

Here’s my practice jam..

Finished a track I’d been working on recently, and decided to put together a wee bandcamp release of things I’ve finished this year. All written and performed with Soundb0ard.